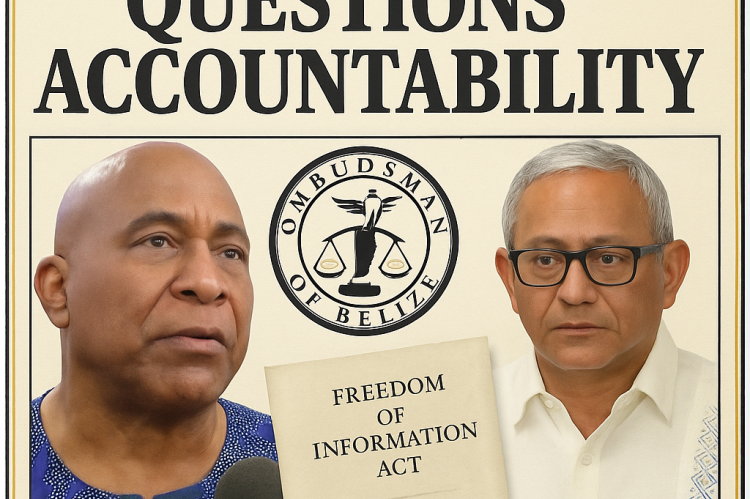

Was the Ombudsman Punished for Doing His Job? FOIA, Attorneys’ Fees, and the Price of Independence

The question now confronting Belize is no longer hypothetical:

Did the Ombudsman lose his post because he insisted on transparency?

When Ombudsman Gilbert Swaso ruled that the Attorney General must disclose attorneys’ fees paid to Marine Parade Chambers and Courtenay Coye LLP—public funds expended in politically sensitive litigation—he crossed an invisible red line.

From that moment, the machinery of the State shifted:

- The government challenged the Ombudsman in court.

- The Prime Minister publicly questioned Ombudsman’s authority.

- The Ombudsman’s contract was allowed to expire without explanation, notice, or parliamentary process.

This sequence is not random. In constitutional analysis, sequence is evidence.

Retaliation Without Saying the Word

No government ever admits retaliation. Instead, retaliation is practiced through:

- Silence;

- Delay;

- Procedural ambiguity;

- Contractual “natural endings.”

But when a watchdog’s enforcement action is followed by removal—or non-renewal—the doctrine of institutional reprisal applies.

Swaso’s own responses are telling. He never retreats from the legality of his decision. He states clearly:

“We acted within the confines of the law… independence of this office was demonstrated.”

That statement alone explains why the executive became uncomfortable.

An Ombudsman who understands his office as independent, not decorative, is a liability to a government allergic to disclosure.

The FOIA Case Was the Trigger

Let us be clear:

This was not about policy.

This was not about competence.

This was about money and secrecy.

The FOIA request concerned legal fees paid by the Government of Belize—fees the public has a statutory right to know. The Ombudsman sided with the citizen, not the Cabinet.

That choice matters.

Once the government chose to litigate against its own Ombudsman, the relationship was effectively poisoned. What followed—the quiet non-renewal—was not administrative tidiness, but institutional punishment.

“Toe the Line or You’re Gone”: The Chilling Message

The most dangerous consequence of this episode is not Swaso’s departure—it is the signal sent to the next Ombudsman:

Exercise independence at your own risk.

That is the textbook definition of a chilling effect.

Oversight institutions do not collapse only when abolished; they collapse when officeholders learn that career survival depends on compliance.

An Ombudsman who must worry about contract renewal cannot be truly independent. That is why international standards reject short, renewable tenures.

Venice Principles, Paris Principles — and Belize’s Failure to Align

Swaso’s intervention here is crucial and sophisticated. He correctly references:

- The Venice Principles (Council of Europe standards for Ombudsman institutions);

- The Paris Principles (UN standards governing National Human Rights Institutions).

Both are explicit:

- Ombudsmen must enjoy security of tenure.

- Tenure should be long, fixed, and non-arbitrary (commonly 6 years);

- Removal or non-renewal must be exceptional, reasoned, and insulated from executive influence.

Belize’s Ombudsman Act, with its 3-year renewable term, fails these standards outright.

Worse still, Belize now seeks to integrate the National Human Rights Institution (NHRI) into the Ombudsman’s office—an institution that must be Paris Principles–compliant to retain international credibility.

You cannot build a human rights institution on executive insecurity.

Mental Health: Another Inconvenient Truth

Swaso’s final reports added yet another layer of discomfort for the administration:

He identified unchecked mental health issues in public service and law enforcement as a human rights crisis.

This was not abstract commentary. It implicated:

- Ministries;

- Heads of Departments;

- Law enforcement command structures;

- The government’s failure to act preventively.

Once again, the Ombudsman did what oversight bodies are meant to do: tell the truth early, before tragedy multiplies.

In governments with mature democratic culture, that earns respect.

In insecure administrations, it earns exile.

The Legal Bottom Line

Let us state this plainly:

- The Ombudsman acted lawfully;

- The Ombudsman acted independently;

- The Ombudsman acted in the public interest.

The response of the State—vagueness, silence, non-renewal, and institutional vacuum—fails every test of good governance.

Whether or not the government admits it, the effect is unconstitutional:

- It undermines oversight;

- It chills independence;

- It weakens FOIA enforcement;

- It corrodes public confidence.

Final Editorial Judgment

This was not an administrative coincidence.

It was a political consequence.

When transparency becomes inconvenient, power retaliates quietly.

When oversight becomes effective, it is made temporary.

Belize should be alarmed—not because an Ombudsman has left, but because the law-abiding conduct of an Ombudsman has become a liability.

That is how democracies don’t fall overnight—

they erode, contract by contract, silence by silence.

- Log in to post comments